I’ve got a complicated relationship with my military service—like trying to explain your first marriage to a room full of therapists with clipboards. I was in the South Dakota Army National Guard for seven years, back when the Cold War was still giving everyone anxiety hives and nuclear winter was a trending fear. I didn’t join because I was itching to wear camo or yell “hooah.” I joined because I wanted to go to college without being financially waterboarded. The Guard gave me a shot—and yes, I also gave a damn about the country and the state I called home.

In 1986, the general consensus was that if World War III didn’t nuke us into oblivion, the draft would return with a vengeance. My recruiter had a tidy little pitch: Guard and Reserve units would be activated as intact squads, not scattered like existential confetti across the front lines. Given that my hometown had more missile silos than grocery stores, it felt like a calculated gamble.

Now here’s the weird part: National Guard units are also technically state militias. That meant we trained for “civil disturbance.” Riot control. You know, the polite way to say “if things go sideways, you might be holding a baton against your neighbor.” My unit—RIP—was based in Sturgis. Yes, that Sturgis. The biker Mecca. The city where leather, engines, and unchecked testosterone form a sweaty summertime trinity.

During the 50th Anniversary Rally, we were prepping like we were about to face Mad Max: Leather Edition. They told us to take our riot gear home “just in case.” I still don’t know how 20-year-old Step-Pope Richard would’ve reacted if ordered to morph into a stormtrooper against a bunch of drunk Harley riders. Probably poorly. It was a simpler time. Fascism was more subtle. Helmets didn’t make you complicit—just sweaty.

Then came Desert Shield. Then Desert Storm. And just like that, the Cold War poker table flipped. I remember a training exercise where a Sixth Army liaison casually mentioned that if Bush had pushed further, units like mine in the Dakotas would’ve been deployed. I signed up for tuition, not trauma. That realization etched itself into my bones. I extended my service a year longer than required, then walked away.

What did I get for my time? Let’s tally it up. My loans shrank. I scored a home loan. I got college credit for pushups (P.E., of course). ROTC courses. Tuition breaks. An enlistment bonus that didn’t suck. No combat, no deployment, no medals—just a knapsack full of benefits and the gnawing knowledge that it could’ve gone very differently.

And that’s why it burns—burns—when politicians like Cynthia Lummis (R-WY) smirk through their dentures while claiming they’d help homeless veterans “if it didn’t cost money.” Lady, we didn’t serve for the savings account. We served because we thought the oath meant something.

Basic Training rewired my survival instincts. It’s like the old frog joke: Bite the head off one every morning and the rest of the day can’t get worse. That’s military conditioning in a nutshell. And even now, I feel an unspoken bond with anyone who’s worn the uniform. I know the acronyms, the ritual of putting on dress blues, the weird way MREs haunt your digestive system.

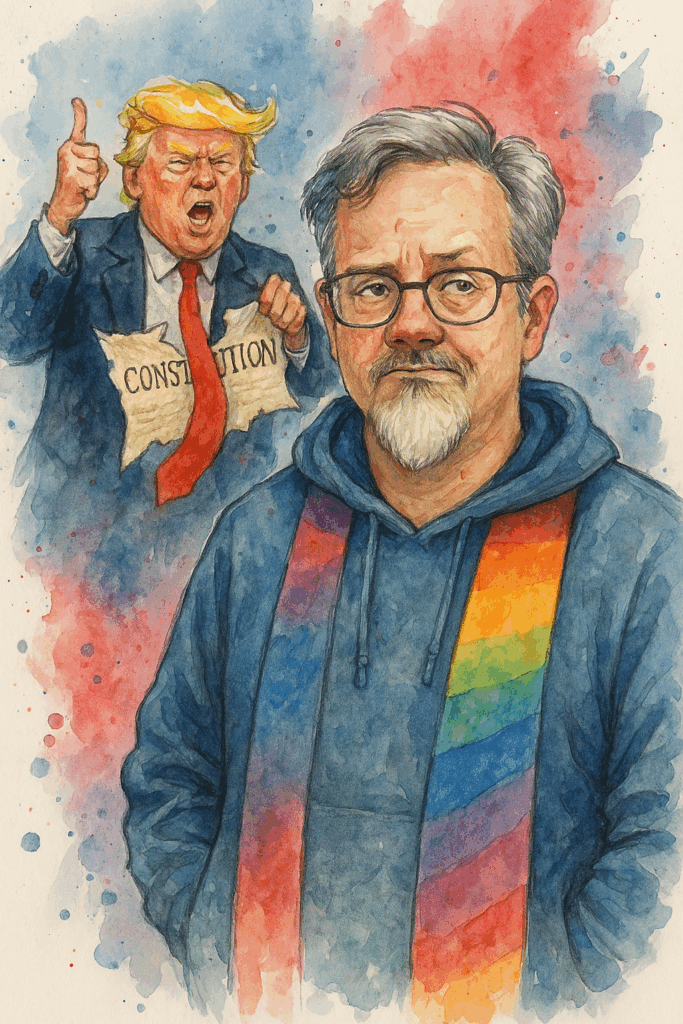

I’m an IT nerd with a Spanish degree, a stage voice, and a vintage Weird Al beret. But I was also a soldier. And I still believe the oath we took—to defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic—wasn’t just cosplay. It was a sacred commitment. That includes questioning illegal orders. That includes calling out abuses of power. That includes knowing that when Abu Ghraib happened, we didn’t just lose global credibility—we torched a moral obligation. The real disgrace wasn’t just the sadists with cameras. It was the officers who should’ve stopped it and didn’t.

Now, we’ve got domestic troops rolling into Los Angeles like it’s Fallujah 2.0, and I’m wondering: Where the hell are the officers screaming “No” from the rooftops? Because if they’re not, they’re not soldiers. They’re just well-armed cowards in costume.

And then there’s the “stolen valor” crowd—keyboard warriors with more flags in their bios than neurons in their cortex—accusing me of faking service because I’m liberal, queer-friendly, or didn’t vote for authoritarian cosplay. Yeah, I wore a beret. It was from Weird Al’s Mandatory Fun tour. Calm down.

The oath alone doesn’t make you honorable. Living up to it does.

For a long time, I skipped Veterans Day discounts. I didn’t feel like I’d “earned” them. I wasn’t deployed. I didn’t want to explain nuance to some guy in cargo shorts. But my wife changed that. She was proud of me. And that made me think maybe I should be, too.

So now, when someone says, “Thank you for your service,” I say, “You’re welcome.”

And I hope—sincerely—that the next generation of uniformed Americans, especially those being handed questionable orders in California right now, will one day be able to say the same… and mean it.