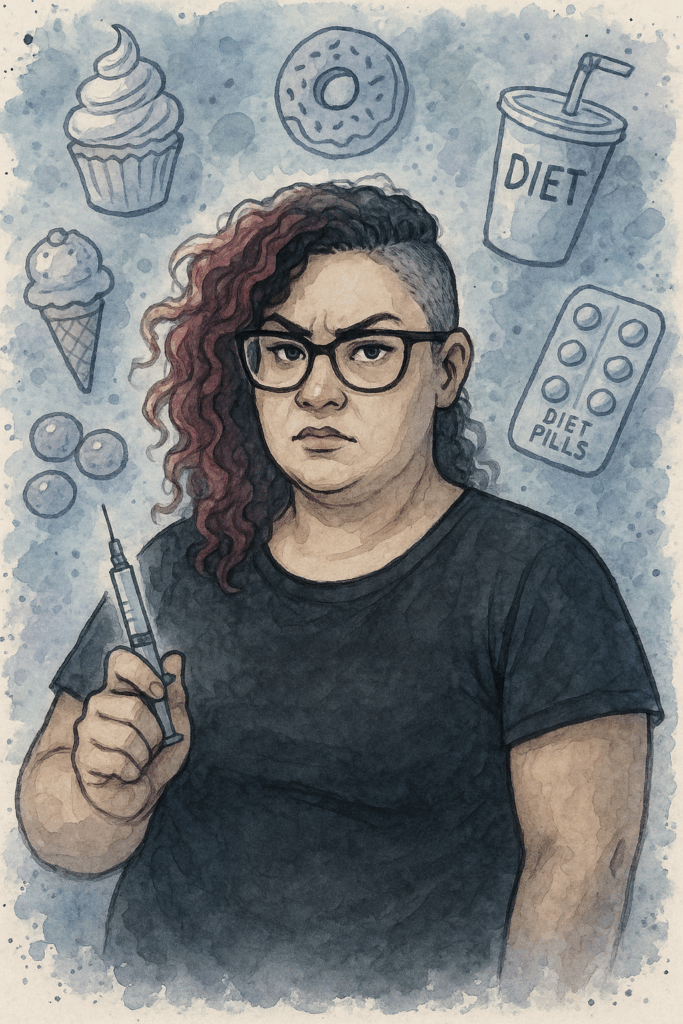

How weight loss drugs, restriction, and moralized food thinking hijack your intuition—and what to do instead

Welcome, dear apostates.

Whether you know it or not, you were probably raised in a cult. Not ours—we’re charmingly unstable and spiritually hydrated. The one you were raised in? Diet Culture: a trillion-dollar, socially reinforced ideology disguised as healthcare.

It preaches salvation through weight loss and atonement through kale. It moralizes food and pathologizes hunger. And like all good cults, it promises that if you just suffer enough, you’ll finally be worthy.

Canonical Doctrine: Be Smaller, Be Better

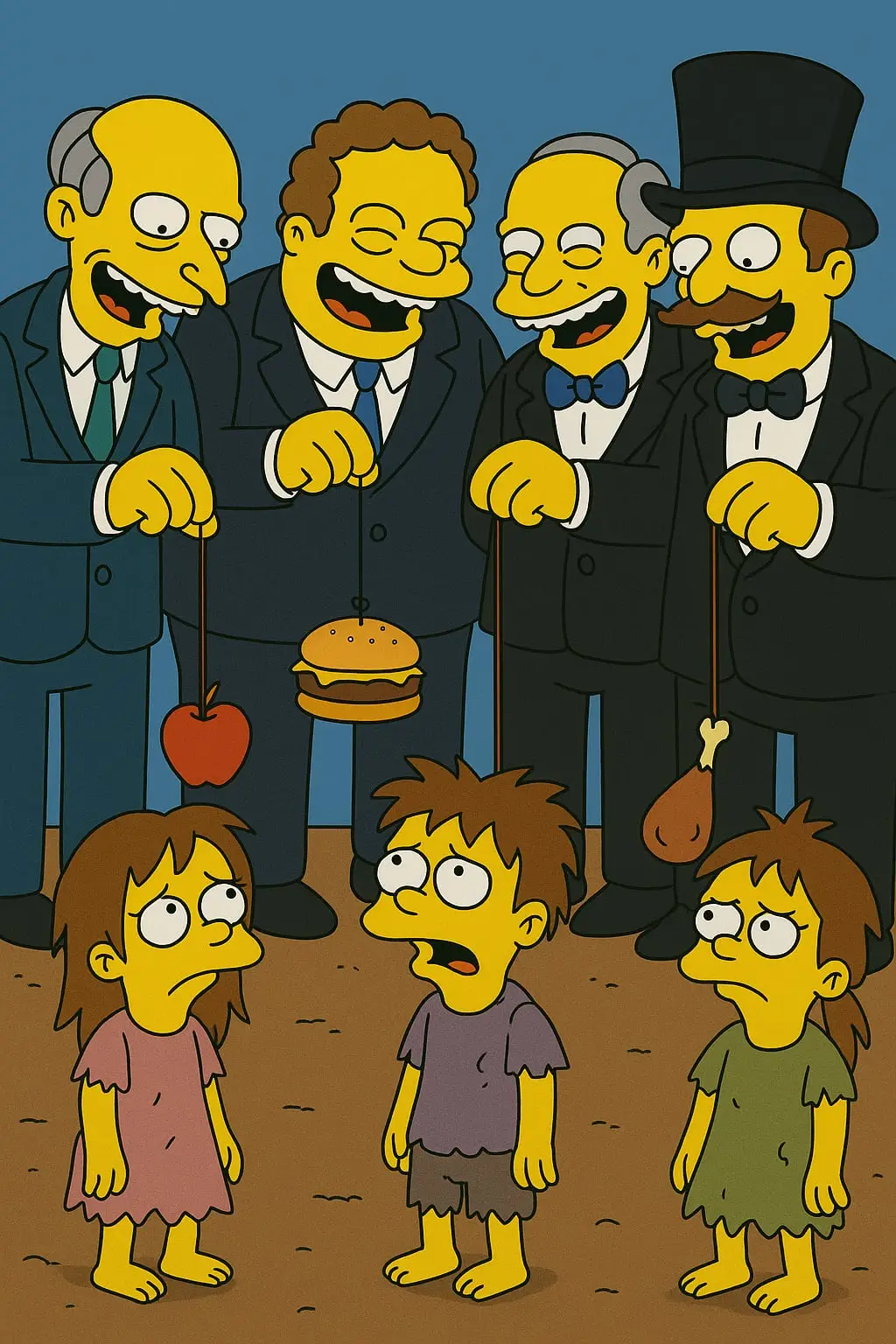

Diet Culture teaches that:

- Hunger is weakness.

- Cravings are moral failures.

- Thinness is virtue.

These messages aren’t accidental—they are strategic, reinforced through decades of advertising, flawed medical training, and pop psychology (Tylka & Calogero, 2011). Even modern pharmaceuticals like GLP-1 inhibitors (e.g., Ozempic) enter with the same sermon: you are too much. Let’s erase you.

But here’s the heresy:

Weight loss doesn’t heal emotional wounds. It doesn’t regulate attachment styles. It doesn’t repair disordered coping. It doesn’t fix capitalism.

Worse, GLP-1 drugs can blunt emotional response (Lee et al., 2023) and disrupt interoceptive awareness—the internal sense that helps us know we’re hungry, full, tired, or sad (Herbert & Pollatos, 2012). That’s not empowerment. That’s numbing with side effects.

A Brief History of Body Shame and Capitalist Bullsh*t

Diet Culture didn’t fall from the sky like an overcooked keto pancake. It was manufactured—for profit, control, and social sorting.

The obsession with thinness as a marker of health? That’s not universal or ancient. It’s a modern invention tangled up in racism, classism, and colonialism. In the early 20th century, white middle-class women were taught that controlling their bodies symbolized moral superiority—while Black, Indigenous, and immigrant bodies were pathologized as “excessive” (Strings, 2019).

Thinness became a tool of social hierarchy—one that said: smaller = more civilized.

Fast forward to now, and we’ve got a $70+ billion diet industry built on this lie—selling shame and scarcity like it’s a wellness smoothie (Marketdata, 2023). And Capitalism? It loves a distracted population. Keeps us too busy counting almonds to burn the whole system down.

And here’s the kicker:

Weight loss isn’t health.

Thinness isn’t a biometric. It’s a body type.

Health is multidimensional—it includes sleep, movement, stress resilience, trauma recovery, access to care, emotional literacy, social support, and yes, joy. There are fat people with excellent cardiovascular health. There are thin people whose internal systems are on fire. Your BMI doesn’t know your cortisol levels.

Most importantly?

Health isn’t a moral obligation. But feeling good is a human right.

Feeling good means being in a body you can trust. It means eating food that doesn’t hurt. It means moving in ways that feel freeing, not punishing.

It means shifting the question from “Am I thin enough?” to “Do I feel like myself today?”

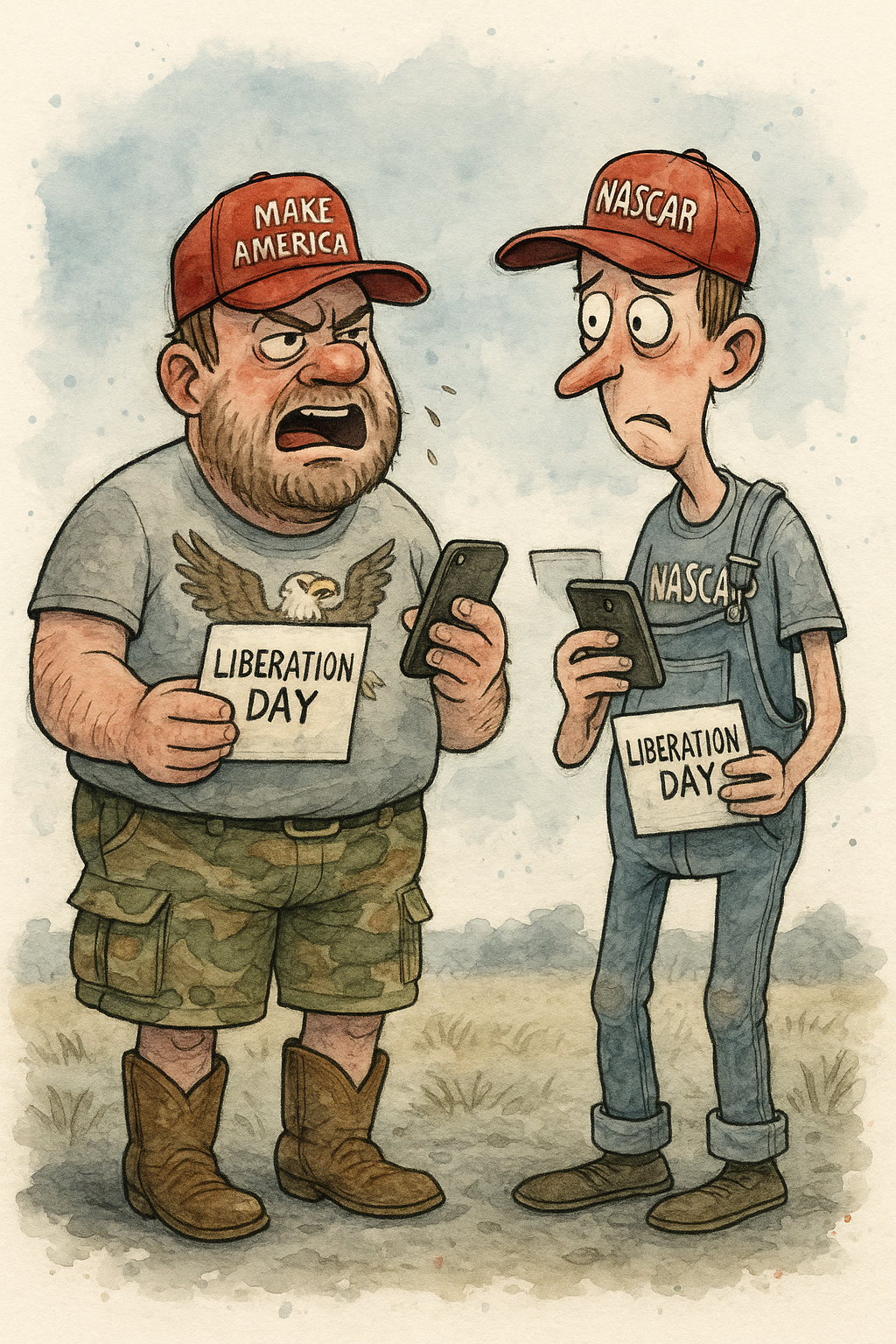

A Modern Distraction Disguised as Reform

Enter the “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) brigade—led by Robert F. Kennedy Jr.—promising to heal the nation by slashing dyes and pushing wearable apps as public health cure-alls. Sounds noble until you realize they’re leaning hard on thinness and regulation theater instead of real healing. MAHA pushes announcements like banning food dyes and stricter labeling, while low-income supports like SNAP, WIC, and environmental protections quietly get axed. In essence, it’s a PR facelift pretending to be a public health plan—thinness as salvation, not spirit.

The Ice Cream Isn’t the Villain—It’s a Messenger

You think you want ice cream? You’re wrong. You want what ice cream used to mean—joy, celebration, safety.

This is what psychologists call emotional eating—but not in the shaming sense. Emotional eating is a natural response to distress when other regulation tools are unavailable (Macht, 2008). It’s not pathology. It’s a coping strategy.

But here’s the kicker:

Comfort foods often don’t deliver on their promises. Studies show that while food can elevate mood briefly, the “comfort effect” fades rapidly and doesn’t outperform neutral foods in the long run (Wagner et al., 2014).

You weren’t craving calories. You were craving connection.

Intuitive Eating Is Not a Cult—It’s a Deprogramming Practice

Intuitive eating (Tribole & Resch, 2020) is not “eat whatever you want, whenever.” It’s an evidence-based framework that reconnects you with your internal cues—hunger, fullness, satisfaction—and strips away diet dogma.

It’s associated with:

- Improved psychological well-being (Bruce & Ricciardelli, 2016)

- Lower disordered eating risk (Tylka et al., 2014)

- Greater body appreciation (Avalos & Tylka, 2006)

And let’s be clear: journaling isn’t about tracking grams—it’s about decoding meaning. Curiosity over control. Reflection over restriction.

“Why did I eat that?” becomes: “What was I needing?”

“I shouldn’t have had that” becomes: “What story did I believe?”

Movement Is Not Penance

In Diet Culture, exercise is punishment. But when decoupled from shame, movement becomes a tool for self-regulation, affect discharge, and embodiment (Pierce & Pritchard, 2010).

Dancing like a weirdo in your kitchen isn’t a workout—it’s somatic resistance.

Your Body Isn’t a Problem to Solve

Let’s end with this:

Your body is not a before picture. It’s not a malfunctioning machine. It doesn’t need fixing—it needs listening.

Bodies aren’t just physical—they are sites of trauma, memory, intuition, and resistance. Treating them like puzzles to be solved erases their humanity (Brown, 2015).

Your body is your home. Don’t outsource its care to an algorithm or a stranger yelling about carbs on TikTok.

Welcome to the Better Cult

We don’t preach discipline. We practice curiosity.

We don’t track sins. We build connection.

We don’t promise thinness. We promise snacks—and they do not come with guilt.

You’re not a failure. You’re recovering from a system that profits from your shame.

Welcome. You’re not alone anymore.

P.S. Why I’m Right About This (and You Can Be Too)

I’m Dr. Jess. I hold a Doctorate in Behavioral Health, a Master’s in Counseling, a Master’s in Education, and a Bachelor’s in Physiology.

I’ve spent over two decades helping people heal their relationship with food, body, and self—not by handing out food rules, but by unraveling the systems that made them necessary in the first place.

I’ve sat with patients sobbing over cookies. I’ve worked with clients gaslit by doctors who prescribed weight loss for pain. I’ve taught trauma-informed behavioral health in clinical settings, corporate boardrooms, and back corners of humanity most people ignore. And through it all, the pattern is the same:

You were never broken.

You were reacting to a broken system.

I’m not here to fix you. I’m here to remind you that you were never the problem.

And to invite you into a better kind of cult—one where your body isn’t up for debate, and joy counts as data.

References:

- Avalos, L., & Tylka, T. L. (2006). Exploring a model of intuitive eating with college women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(4), 486–497.

- Bruce, L. J., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2016). A systematic review of the psychosocial correlates of intuitive eating. Journal of Eating Disorders, 4(1), 1-12.

- Brown, B. (2015). Rising Strong. Spiegel & Grau.

- Herbert, B. M., & Pollatos, O. (2012). The body in the mind: On the relationship between interoception and embodiment. Topics in Cognitive Science, 4(4), 692–704.

- Lee, Y. et al. (2023). GLP-1 receptor agonists and their effects on emotional regulation: A review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 160, 85-92.

- Macht, M. (2008). How emotions affect eating: A five-way model. Appetite, 50(1), 1–11.

- Marketdata. (2023). U.S. Weight Loss Market: Forecasts and Trends.

- Pierce, E., & Pritchard, M. (2010). Exercise dependence, self-esteem, and body satisfaction in college-aged women. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 2(2), 62–69.

- Strings, S. (2019). Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia. NYU Press.

- Tribole, E., & Resch, E. (2020). Intuitive Eating (4th ed.). St. Martin’s Essentials.

- Tylka, T. L., & Calogero, R. M. (2011). Dieting, disordered eating, and self-objectification in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 103–112.

- Tylka, T. L., et al. (2014). Intuitive eating and its psychological benefits: A review. Nutrition and Health, 23(3), 192–201.

- Wagner, H. S., et al. (2014). The myth of comfort food. Health Psychology, 33(12), 1552–1556.