I was probably five when I first asked the question that would shape the next fifty years of my life: “Why can’t people just be nice to each other?” It seemed like such a simple thing. Be kind. Don’t hurt each other. Share your toys. The usual kindergarten wisdom that adults nod at and then promptly ignore while building nuclear weapons.

Growing up in the ’80s with a view of the runways that made me—well, us collectively—the USSR’s number two target will do things to your developing philosophy. There’s something profoundly absurd about navigating high school while knowing that somewhere across an ocean, people you’ve never met have pointed civilization-ending missiles at your neighborhood. The cognitive dissonance is spectacular: worrying about algebra tests and dating while the evening news explains how we might all die in nuclear fire because adults couldn’t figure out how to be nice to each other.

Somewhere in that contradiction, between the first-grade traumatizing incident that may or may not have been a supernatural experience or my first bipolar episode—my realization that I had just experienced a 4D version of Donnie Darko decades before it came out—a philosophy began to take shape. Not all at once; nothing that useful ever happens quickly. It grew organically through forty years of watching humanity struggle with the basic concept of not being terrible to each other.

What emerged from all that thinking might be foundational philosophical concepts. Or elaborate mythology I tell myself to make sense of a senseless world. Or both. Or neither. It could all be sophisticated nonsense dressed up in academic language. But here’s what crystallized from decades of wrestling with the fundamental question of human decency:

The Original Wholeness

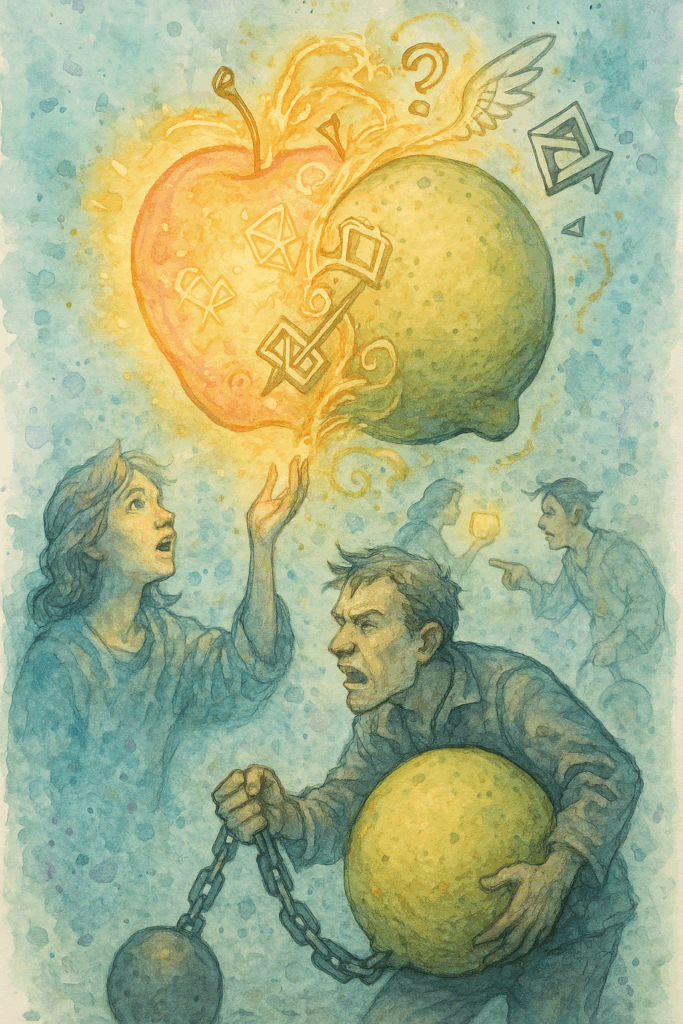

In the beginning, there was the Citrifruit of Balance—and yes, I’m aware this makes no botanical sense since both apples and lemons are already fruits, but that’s a perfect example of how absurd everything is, so we’re keeping it. A perfect unity containing both the sweet possibility of what could be and the sour reality of what actually is. This wasn’t some mystical revelation; it was the natural state of a mind desperately trying to reconcile “people should be kind” with “people keep building bigger bombs to murder strangers more efficiently.”

The Citrifruit represented that brief, shining moment before you realize the world is fundamentally broken—when you still believe the contradiction might resolve itself if you just think about it hard enough. It’s the philosophical equivalent of being five years old and assuming adults have everything figured out, right up until you notice they’re all just tall children with credit cards, anxiety disorders, and an alarming enthusiasm for making other people’s lives miserable.

The Great Splitting

The Citrifruit couldn’t hold because reality is a bastard with commitment issues. Reality has a way of insisting on its own terms, and those terms apparently include war, suffering, and people who leave their shopping carts loose in parking lots. The split was inevitable—one part becoming the Golden Apple of chaotic possibility, the other crystallizing into the Dull Lemon of structured reality.

The Golden Apple carries all the “what ifs” and “why nots”—the creative chaos that whispers dangerous ideas like “maybe things could be different” and “what if we tried being kind for once?” It’s the part that refuses to accept that suffering is inevitable, that keeps generating new possibilities even when the old ones have exploded into flaming wreckage. The Apple is either admirably persistent or clinically delusional, depending on your perspective.

The Dull Lemon, meanwhile, handles the paperwork for humanity’s ongoing clusterfuck. It’s the part that documents all the ways kindness gets bureaucratized into meaninglessness, that maintains the filing systems for fifty years of accumulated disappointment. It knows exactly how many times “be nice to each other” has been tried and failed, and it has the forms to prove it, organized by date and level of catastrophic failure.

They’re not enemies, these two aspects—they’re more like cosmic siblings forced to share a philosophical bedroom while the world burns outside. The Apple finds the Lemon insufferably pessimistic; the Lemon finds the Apple exhaustingly naive. But they’re stuck with each other. Without the Lemon’s structure, the Apple’s chaos becomes meaningless noise. Without the Apple’s possibility, the Lemon’s order becomes the sterile despair of someone filing reports on the apocalypse.

Living the Split

Most of us carry both the Apple and the Lemon, though we usually favor whichever one hurts less on any given day. The Apple people are the ones still trying to save the world with good intentions and positive thinking, bless their demented little hearts. The Lemon people are the ones who’ve given up on salvation and settled for competent administration of the disaster, which is arguably more useful but significantly less fun at parties.

But here’s what fifty years of thinking about this shit has taught me: the split isn’t a problem to be solved. It’s a feature, not a bug. The tension between possibility and reality, between chaos and order, between “what if” and “what the hell is wrong with people”—that’s where the interesting stuff happens, assuming you have a high tolerance for existential nausea.

The Golden Apple reminds us that things could be different, even when all evidence suggests otherwise. The Dull Lemon reminds us that they probably won’t be, but we still have to file the paperwork and pay our taxes while civilization collapses around us. Together, they form something like a complete approach to existence: hopeful enough to keep trying, realistic enough to stock up on alcohol when it doesn’t work.

The Practice of Balance

You can’t reunite the Citrifruit—that particular innocence died the moment you realized the world is simultaneously beautiful and terrible, meaningful and absurd, worth saving and absolutely fucked. But you can learn to juggle both aspects without completely losing what’s left of your sanity.

Some days, let the Golden Apple run the asylum. Dream impossible dreams about kindness winning while doom-scrolling through evidence to the contrary. Plan revolutions in human decency that will crash and burn spectacularly, but hey, at least the wreckage will be colorful. Generate wild possibilities knowing they’ll splatter against reality like roadkill on the highway of good intentions.

Other days, let the Dull Lemon manage the damage control. File your taxes while civilization crumbles. Document your failures with the obsessive precision of someone cataloging the apocalypse. Maintain the systems that keep society lurching forward like a drunk driver who hasn’t hit anything important yet. Accept that most people are bastards, but you can still try not to be one—if only because spite is a surprisingly effective motivator.

The wisdom isn’t in choosing one over the other—it’s in recognizing which brand of existential nausea you’re equipped to handle today. Sometimes the world needs more chaos, more Golden Apple energy to burn down the stupid parts. Sometimes it needs more structure, more Dull Lemon competence to prevent the collapse from happening before we’ve had our coffee.

And occasionally, if you’re very lucky or your medication is properly calibrated, you catch a glimpse of what the original Citrifruit might have been—that brief moment when possibility and reality stop trying to murder each other and remember they’re stuck in this mess together.

The question I started with at five—”Why can’t people just be nice to each other?”—still doesn’t have a satisfying answer. After fifty years of investigation, the best I can offer is that people are bastards, the world is broken beyond repair, and asking the question is the only thing that keeps us from becoming complete monsters ourselves. It’s not much of a philosophy, but it’s the only one that works when you’d rather not exist but have to anyway.