Indigenous Environmentalism in Wyoming

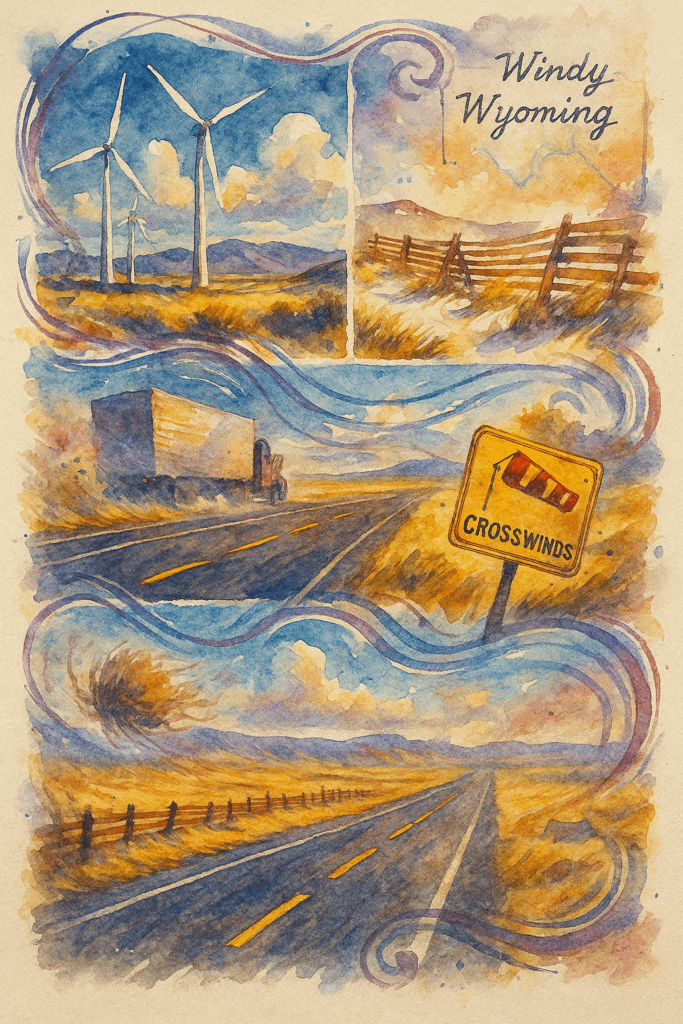

My wife always says, as the Wyoming wind whistles through the misaligned insulation that keeps our window from sealing, “One day we’ll wake up and the house will be in Siberia!” Or sometimes Serbia—depends on the pitch of the whistling. Out on the high plains, the wind never shuts up. It tears across the sagebrush like it’s got an agenda—which, in a way, it does. It remembers things. Old things. Stories from before borders, before pipelines, before Wyoming was a shape on a map.

For the Lakota—and for the other Plains Nations who’ve lived with this wind since memory began—the land isn’t scenery; it’s kin. The hills are elders, the rivers are arteries, the bison are prayer made visible. Environmentalism isn’t a political stance; it’s family loyalty. You don’t recycle to feel virtuous—you do it because you wouldn’t dump trash in your grandmother’s lap.

That’s what people miss about this place. They call Wyoming conservative because it votes that way, because it wears grit like a badge. But there’s a deep liberalism here—not legislative, moral. The sense that freedom and responsibility are the same hand, palm and knuckle. You don’t own the land; you borrow it from the future. You don’t control nature; you participate in it.

Modern environmentalism talks about sustainability like it’s new, but the Lakota, Shoshone, Arapaho, Crow, Cheyenne, and their relatives have practiced it since before English had a word for “carbon.” The principle fits on a bumper sticker: everything you take, you owe back.

It’s not utopian; it’s brutally practical—and just as true for cowboys and coal miners. Winters kill. Droughts bite. Fire resets the ledger. The earth doesn’t need your feelings—and doesn’t care about them anyway. That’s our Cult-of-Brighter-Days flavor: compassion with dirt under its nails. “Failure is mandatory” applies to ecosystems, too; you learn from collapse, not control. The prairie burns, the grass returns, the circle keeps circling.

Drive through central Wyoming and you’ll see it: an uneasy truce between human ambition and ancient patience. Wind farms spin above old bison routes. Snow fences stand just enough in the wind to keep drifts off the highway (mostly). Somewhere between those contradictions, the Lakota idea still hums: Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ—“all are related.” Not just your tiyospaye, your extended family, but all the other people, the four-leggeds, the winged ones, the wind in the trees—and their spirits. We’re in this together, which means we should be pulling for each other. It’s not a metaphor. It’s land management disguised as prayer.

Maybe that’s where Wyoming’s hidden liberalism really lives—not in ballots or slogans, but in the stubborn decency of people who still talk to the wind before they build. Out here, even the most pragmatic rancher knows better than to pick a fight with the river.

The wind’s still talking, after all. Listen long enough and you realize it isn’t warning you; it’s inviting you to remember whose bones you’re standing on.